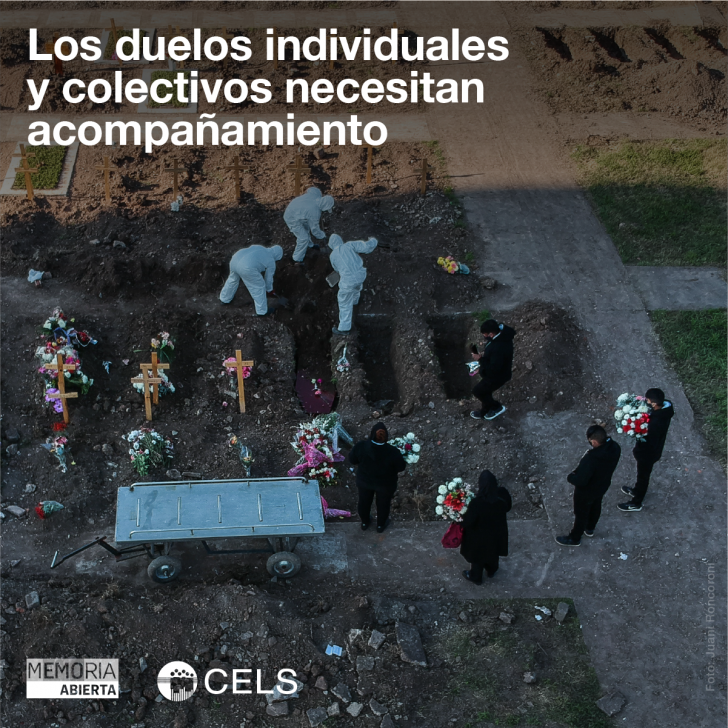

From the moment a case is suspected, the ongoing pandemic limits people’s contact with their friends and families. The symptoms, the test results, the hospitalization, the intensive care and, when it occurs, the death and the impending decision on the fate of the deceased according to one’s beliefs, are processed without the possibility of dealing with it as a group, in the way that each community would.

The final farewell to those who part is essential. For people, grieving is an extreme life circumstance that requires group support and community. For society, funeral rites are where the loss of a member is processed. Wakes, funerals or whichever the chosen ceremony are meant to support family members and friends, and also mark the completion of the passage of a person known and loved by their own. We do not yet know what the consequences the inability to say goodbye to those who die in times of pandemic will be for the affected people and for society, whether as a result of the virus or not.

The State is making efforts to protect the population from massive contamination and from the saturation of the health system. Faced with what is inevitable –fear, pain, discomfort– mournings must also be cared for and accompanied.

Diagnosis, isolation, hospitalization, critical care, and death are not experienced by all in the same conditions, with the same material resources or with the social resources that often improve the conditions of these instances.

Mourning must be considered as a right, which cannot be reduced to an individual question that unfolds according to one’s economic conditions, nor can it depend on whether we know how to find a more amicable path than the standard one.

The way in which isolation determines how illness and death are experienced, on the part of the virus victim and on the part of their loved ones, requires clear, general, and homogeneous guidelines from the State for public and private institutions involved in the circuits that deal with illness and death. Without these guidelines, unequal impacts are deepened and we risk consolidating arbitrary regulations that lack scientific substantiation or that overlook some of the aspects at stake.

Faced with the surge of cases and the possible collapse of the health system, there is a risk that the mechanisms and circuits generated by the State to face the crisis be so rigid and predetermined that they overlook the singularity of each mourning person and their rights. We have heard of and intervened in decisions that were made, or were attempted to be taken, invoking, for example, an alleged obligation of cremation, which is not such, and that compose a threat to the right of people to decide their own final destination and that of their loved ones. These guidelines would also serve as support for health system workers, who witness and play a role in these painful situations.

The State is in the difficult situation of adopting strict distancing measures to preserve health. At the same time, it is making decisions by which it enables different types of human contacts because it considers them essential. These essential contacts should include farewells and allow that time be spent with those who are about to die or those who have just parted.

Parting rites are diverse and there are differences in practices and traditions, related to ideas and beliefs about materiality and transcendence. This must be recognized and respected by the State, so that the communities can perform the rites they have built.

With all the protection mechanisms necessary to avoid new cases, a last glance at the person who has died should be included as an option for those who need it, since that proof of the reality of death is what instills the loss and gives way to mourning.

Not seeing the corpse can lead – consciously or unconsciously – to the illusion or the fantasy that a mistake has been made and other situations that pave the way for a prolonged grief process. The absence of a last glance to the departed causes the effect of a disappearance and the grave complications this implies for mourning. As we all know, today the most frequent scenario is that people see their loved ones just prior to hospital admission and, if death occurs, they receive a closed coffin. That lack of middle instance between seeing a living being and then seeing a sealed coffin containing that person’s remains should not become the norm.

The decision on who participates in the wakes, cremations or burials, as well as the number of mourners allowed, should be made with the active participation of the deceased’s nucleus so that the relatives and friends of the deceased may request an adaptation of the standardized procedure if they require so.

The aforementioned aspects carry a traumatic potential for people whose loved ones are dying or have died from COVID-19 and whose dismissal rituals were conditioned by social distancing. In the case that they should express this need, the State should offer psychological assistance and social support –and when possible, facilitate spiritual and cultural-community assistance– as it has done in other moments of social upheaval.

If the restrictions remain in place, it is necessary for the State to take a public stand regarding the suffering that the abbreviation or modification of funeral rites implies for families and friends. It is also imperative that the State limit the duration of these restrictions to a minimum and grant them a meaning in terms of collective care.

A state framework that allows a collective processing of these diverse deaths is necessary. The aim should be to accompany families and individuals so that they are not alone in the face of the death of their loved ones and to give these deaths a shared meaning, placing them in the exceptional situation that we are going through.

From this perspective, public policies could offer means of collective memorialization, such as the publication and / or dissemination of the names of deceased persons – with the consent of their relatives – in the media, the production of programs, pieces on the radio television and digital media that recover the life trajectory of the people who died as well as signs, commemorations, tributes or acts of recognition. As our recent history shows, memory as a social practice also acts in favor of healing and repairing common traumatic experiences.

Without a doubt, the regulation of all aspects of caring for people who suffer from the disease and die of COVID-19 is a difficult task in every single step along the way. That is why this task must be approached by the national State in the most general scope of guidelines and coordinates of action, in order to generate a homogeneous and common starting point, which will then be adapted according to the particularities of each context.

Some teams of health workers and social and academic organizations have been through experiences that can guide and support the State in this work during this exceptional, specific and somehow novel context for all. As in other moments of our recent history, the intervention of the State is fundamental today to guarantee the right to mourning, reparation and memory for families and for those who perished during the pandemic.

CELS

Photo: Juani Roncoroni