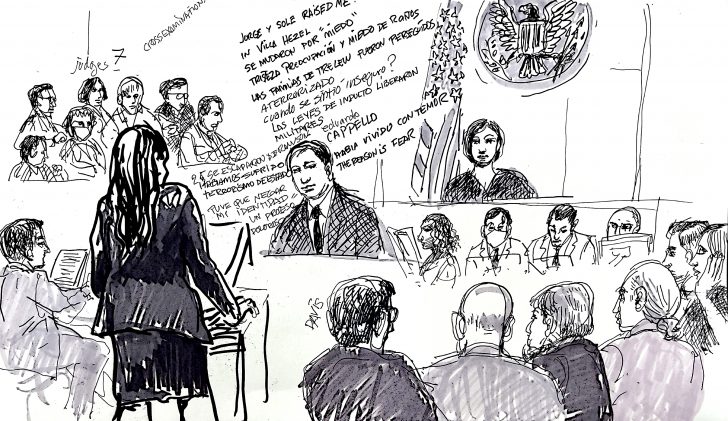

Drawing: Carlos Llerena Aguirre

Day 3 – Wednesday, June 29, 2022:

Upon his return, he was charged with guarding the 19 prisoners. He reported that his interactions with the prisoners were minimal until August 22, when while completing paperwork at 3:00 a.m. a sailor indicated Mr. Bravo needed to go see the prisoners. Mr. Bravo got up, strapped on his gun, and walked to the cell block.

Drawing positions on a visual layout of the premises, Mr. Bravo testified that when he entered, corporals Marandino and Marchan were guarding the prisoners. Marchan asked Mr. Bravo if he could leave because he felt ill. He departed around the same time Sosa, Del Real, and Herrera entered. Marandino told Mr. Bravo that the prisoners were trying to communicate with each other, and Sosa ordered the prisoners to be released from their cells. Mr. Bravo picked up Marchan’s machine gun he had left behind, and Del Real took Mr. Bravo’s pistol. Mr. Bravo testified that Marandino opened the cells and then Sosa ordered the prisoners to stand outside. He recounted that Sosa paced up and down the hallway between the two rows of prisoners, lecturing them loudly. When Sosa returned to the front, Mr. Bravo said things escalated quickly with Sosa’s knees buckling and prisoner Pujadas grabbing Captain Sosa’s .45 caliber pistol. Mr. Bravo indicated he does not recall seeing Pujadas move before grabbing the gun and shooting. Mr. Bravo thought he saw the flame explode from the end of the pistol twice, and believed it was pointed in his direction. Then, Mr. Bravo testified it seemed as if all the prisoners moved toward him at once, leaving him no time to deliberate; his only thought was: “I [have] to stop them.” Mr. Bravo described his shooting as a split-second reaction, while explaining that he shot high to avoid hitting Sosa. In the moments following the shooting, Mr. Bravo was “overwhelmed by the stench of gunpowder and smoke.” He testified that he called for guards and medics. In the aftermath, he was isolated for days pending an investigation.

When shown a report published by the Argentine military in December 1972 which concluded that he complied with his duties and should not be punished, Mr. Bravo said he did not participate in drafting the “top secret” document or gain access to it until 2009. Mr. Bravo disputed the accuracy of several portions of the report, including its claim that he—not Sosa—was the officer who ordered that the prison cells be opened.

Mr. Bravo explained that after the incident, he remained in Argentina for four months before being transferred to the United States, where he eventually founded various companies that were publicly registered under his name and address.

Later, Plaintiffs’ counsel directed Mr. Bravo to redraw the positions of all parties the moment before the shooting, then highlighted inconsistencies with what he drew in a previous deposition. While this drawing depicted the prisoners facing each other, his prior drawing showed them facing the officers. And while Mr. Bravo testified today that prisoner Pujadas fired two shots, he previously claimed only one shot was fired. When asked about his difficulty remembering the number of bullets fired, Mr. Bravo exclaimed: “don’t play with my mind!”

Mr. Bravo testified that the officers involved in the incident were separated during the investigation that followed, and even when rejoined for the reenactment they did not discuss anything. When asked if the investigation and subsequent report were performed under military dictator Alejandro Agustín Lanusse, Mr. Bravo expressed displeasure with the use of the term “dictator,” indicating that Lanusse was a dictator “only for the opposition.”

The jury watched a video deposition of Dr. Julio Cesar Ulla, brother of victim Jorge Ulla. Dr. Ulla revealed that after learning of his brother’s tragic death, his family received the body which contained two wounds, one surrounded by soot on the chest and another on his thigh. He reported that the military failed to disclose a cause of death and no doctor would perform an autopsy for fear of reprisal. When Dr. Ulla and his family sought justice, they were repeatedly harassed, stalked, and attacked. In one such attack at the funeral procession for his brother, Dr. Ulla recounts that he clung to his brother’s coffin as state security forces bore down on those gathered, fearing that they would take his brother’s body as well as his life.

Forensic pathologistDr. William Anderson explained that the tattooing caused by soot left on victim Jorge Ulla’s chest wound could only be caused by “press contact.” He opined that the gunpowder grains listed on victim Ruben Bonet’s autopsy were also consistent with a close-range gunshot wound. Under cross-examination, Dr. Anderson acknowledged he was not present during the autopsy, had only reviewed the unofficial report, and did not know the credentials of the examiner who performed the autopsy nor whether the body had been altered beforehand.

The jury watched the video deposition of Miguel Marileo, a carpenter who constructed coffins in Trelew. He described being forced to visit the Almirante Zar Naval Base in the middle of the night following the massacre, where he saw three wounded survivors “moaning” on gurneys and 16 naked dead bodies. Two female bodies particularly stood out to him: one visibly pregnant with gunshot wounds from the breasts down, and one with a single wound at the nape of the neck. After completing his work at the prison, he claimed to have been threatened by a military officer to never disclose what he had witnessed, and to remember he has a son.

The jury heard the video deposition of Corporal Carlos Marandino, who recalled Mr. Bravo ordering him to open the prison cells and then leave. When he returned a short while later, he said Mr. Bravo told him to verify the prisoners’ bodies. Mr. Marandino testified that he later returned to Argentina to stand trial as he had nothing to hide.

Finally, Marcela Santucho’s video deposition was played for the jury. The daughter of Trelew victim Ana Maria Villarreal de Santucho, she explained that after learning of her mother’s tragic death her family was subject to harassment and kidnapping. She recounted a difficult childhood, culminating in seeking exile in Switzerland.